Is Iraq Better Off Now Than Before Bush's Invasion & Occupation?

Tuesday, December 26, 2006

Sunday, December 24, 2006

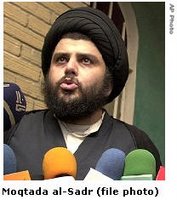

Sadr and his Al Mahdi Army Essential to Governing Iraq

Shiite politicians met with Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani in this Shiite holy city, and then said they had thrown their support behind Sadr, who demands a withdrawal of U.S. troops from Iraq rather than the temporary increase under consideration in Washington. Haider Abadi, a leader of Shiite Prime Minister Nouri Maliki's Islamic Dawa Party:

The Sadr movement is part of Iraqi affairs. We won't allow others to interfere to weaken any Iraqi political movement.Ali Adeeb, another member of the Dawa Party, said Shiite leaders, including the prime minister, would resist U.S. efforts to sideline Sadr and his Al Mahdi army.

The Iraqi government decides what it thinks is necessary for the interest of the political process.He added that Sadr's participation was essential to improve Iraq's political and security problems.

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

Baghdad's Deck Furniture

The prestigeous think tank known as The International Crisis Group doesn't think Baker and Hamilton's ad hoc Iraq Study Group is realistic about the so-called elected parliamentary government in Baghdad. It states that it is past time to make

an honest assessment of where things stand. Hollowed out and fatally weakened, the Iraqi state today is prey to armed militias, sectarian forces and a political class that, by putting short term personal benefit ahead of long term national interests, is complicit in Iraq’s tragic destruction. Not unlike the groups they combat, the forces that dominate the current government thrive on identity politics, communal polarisation, and a cycle of intensifying violence and counter-violence. Increasingly indifferent to the country’s interests, political leaders gradually are becoming warlords. What Iraq desperately needs are national leaders.

Two consequences follow.

- The first is that, contrary to the Baker-Hamilton report’s suggestion, the Iraqi government and security forces cannot be treated as privileged allies to be bolstered; they are simply one among many parties to the conflict. The report characterises the government as a “government of national unity” that is “broadly representative of the Iraqi people”: it is nothing of the sort. It also calls for expanding forces that are complicit in the current dirty war and for speeding up the transfer of responsibility to a government that has done nothing to stop it. The only logical conclusion from the report’s own lucid analysis is that the government is not a partner in an effort to stem the violence, nor will strengthening it contribute to Iraq’s stability. This is not a military challenge in which one side needs to be strengthened and another defeated. It is a political challenge in which new consensual understandings need to be reached. The solution is not to change the prime minister or cabinet composition, as some in Washington appear to be contemplating, but to address the entire power structure that was established since the 2003 invasion, and to alter the political environment that determines the cabinet’s actions.

- The second is that it will take more than talking to Iraq’s neighbours to obtain their cooperation. It will take persuading them that their interests and those of the U.S. no longer are fundamentally at odds. All Iraqi actors who, in one way or another, are participating in the country’s internecine violence must be brought to the negotiating table and must be pressured to accept the necessary compromises. That cannot be done without a concerted effort by all Iraq’s neighbours, which in turn cannot be done if their interests are not reflected in the final outcome. For as long as the Bush administration’s paradigm remains fixated around regime change, forcibly remodelling the Middle East, or waging a strategic struggle against an alleged axis composed of Iran, Syria, Hizbollah and Hamas, neither Damascus nor Tehran will be willing to offer genuine assistance. Though they may indeed fear the consequences of a full-blown Iraqi civil war, both fear it less than they do U.S. regional ambitions. Under present circumstances, neither will be prepared to save Iraq if it also means rescuing the U.S.

There is no magical solution for Iraq. But nor can there be a muddle-through. The choice today could not be clearer. An approach that does not entail a clean break vis-à-vis both Iraq and the region at best will postpone what, increasingly, is looking like the most probable scenario: Iraq’s collapse into a failed and fragmented state, an intensifying and long-lasting civil war, as well as increased foreign meddling that risks metastasising into a broad proxy war. Such a situation could not be contained within Iraq’s borders. With involvement by a multiplicity of state and non-state actors and given that rising sectarianism in Iraq is both fuelled by and fuels sectarianism in the region, the more likely outcome would be a regional conflagration. There is abundant reason to question whether the Bush administration is capable of such a dramatic course change. But there is no reason to question why it ought to change direction, and what will happen if it does not.

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

Iraqi Army Doesn't Contain the Answer

| Nicole Stracke is a researcher in the Security and Terrorism Program at the Gulf Research Center in Dubai. She writes for Arab News: |

|

Sunday, November 26, 2006

A Ballotocracy is not a Democracy

Who's in Charge, Here?

Association of Muslim Scholars'(AMS) Suleiman Harith al-Dhari, Iraq's leading Sunni cleric, who is wanted under an arrest warrant issued this month for inciting sectarian violence, accused the government on Saturday of bias.

Association of Muslim Scholars'(AMS) Suleiman Harith al-Dhari, Iraq's leading Sunni cleric, who is wanted under an arrest warrant issued this month for inciting sectarian violence, accused the government on Saturday of bias. Radical Shi'ite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr, whose Baghdad powerbase of Sadr City was the target of Thursday's bombs which killed 202 people, urged Dari on Friday to issue a fatwa, or religious ruling, prohibiting the killing of Shi'ites.

Radical Shi'ite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr, whose Baghdad powerbase of Sadr City was the target of Thursday's bombs which killed 202 people, urged Dari on Friday to issue a fatwa, or religious ruling, prohibiting the killing of Shi'ites. Sadr's aides also threatened to pull out of the government if Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki went ahead with a planned meeting with U.S. President George W. Bush in Jordan next week.

Sadr's aides also threatened to pull out of the government if Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki went ahead with a planned meeting with U.S. President George W. Bush in Jordan next week.

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Maybe NeoCons Didn't Care About What Followed Saddam

Interesting discussion of David Wurmser in Dick Cheney's Office:

Like Hannah, who came to the OVP from the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Wurmser traipsed a roundabout path to Cheney’s staff: He worked with Hannah at WINEP in the 1990s, and then went to AEI, where he directed Middle East affairs, to the Pentagon’s Office of Special Plans, to John Bolton’s arms control shop at the State Department, and then to the OVP.

Even among ardent supporters of Israel, Wurmser -- and his wife, Meyrav, who runs the Hudson Institute’s Middle East program -- is considered an extremist. In 1996, the Wurmsers, Perle, and Feith co-authored the famous “Clean Break” paper for then–Prime Minister Bibi Netanyahu, which called for radical measures to redraw the map of the entire Middle East (Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Palestine) to benefit Israel.

Later, in a series of papers and a book, Wurmser argued that toppling Saddam was likely to lead directly to civil war and the breakup of Iraq, but he supported the policy anyway:

The residual unity of [Iraq] is an illusion projected by the extreme repression of the state.

be ripped apart by the politics of warlords, tribes, clans, sects, and key families. Underneath facades of unity enforced by state repression, [Iraq’s] politics is defined primarily by tribalism, sectarianism, and gang/clan-like competition.

The issue here is whether the West and Israel can construct a strategy for limiting and expediting the chaotic collapse that will ensue in order to move on to the task of creating a better circumstance.

Sunday, November 12, 2006

One Militia Thug Begets Another Militia Thug

As the White House begins to rethink its policy on Iraq, savage new warlords are battling for power and the country is starting to splinter.

As the self-appointed defender of his Shia kith and kin, his nom de guerre is "The Shield". But to his Sunni foes – and many of his own people – only one name does justice to the savagery with which Abu Deraa wages Iraq's sectarian war. He is, they say, the "Shia Zarqawi".

Less than six months after an American airstrike ended Abu Musab al Zarqawi's campaign of Sunni terror, an equally brutal fanatic has emerged on the other side of the religious divide. Abu Deraa's trademark method of killing is a drill through the skull rather than a sword to the neck, but his work rate is just as prolific as the former al-Qaeda leader's and shows the same diabolical artistry.

In the past year, he and his followers are thought to have murdered thousands of Sunnis, their victims' bodies symbolically dumped in road craters left by al-Qaeda car bombs. The rise of monsters such as Abu Deraa is another blow to American hopes that Zarqawi's death, in June, would halt the sectarian violence, which now regularly claims 100 lives a day.

In the strategy rooms of Baghdad's Green Zone, the question of how to stop the violence escalating into civil war has acquired renewed urgency since President George W Bush's losses in last week's US midterm elections, and his sacking of the defence secretary, Donald Rumsfeld.

Yet, according to diplomats, the Green Zone is no longer the powerhouse of bright ideas for the future of Iraq that it once was. Until as recently as last year, every ambitious state department intern and junior Foreign Office mandarin was keen to do at least a six-month stint there, keen to help forge democracy in one of the toughest environments ever. Today, though, the brightest and the best and have left, giving it the atmosphere of a place being wound down. Few up-and-coming diplomats, it seems, want "Iraq 2006" on their CVs, much less "Iraq 2007". One insider:

Working there is becoming like an albatross around people's necks. The feeling is that it doesn't matter how many hours a day they do, it won't make any difference. And nobody wants to be around if they end up getting helicoptered out, Saigon-style.

Yet, while Abu Deraa may have replaced Zarqawi at the top of the American wanted list, Iraq's Shia-dominated government has shown a marked reluctance to sanction the kind of large-scale operation necessary to arrest him in his stronghold of Sadr City, a vast Shia slum in east Baghdad. Taking action against him could cost it valuable support among other Shia militias who, despite official disdain for Abu Deraa's bloodthirstiness, value the fear that such a loose cannon inspires in their enemies.

The worsening of inter-religious- bloodshed reflects badly on the Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Maliki, whose chief task when he took power in June was to win back Sunni confidence in the political process by stamping out the state's tacit backing of Shia militias such as the Mehdi Army.

Yet, increasingly, men such as Abu Deraa appear to operate beyond anyone's control at all. He is among at least 20 former Mehdi Army commanders who are pursuing their own agendas, sometimes sectarian, often simply criminal. The former commander, Moqtada al Sadr, may be a thug himself, but at least he represented a single, identifiable authority. If dozens of freelance players emerge alongside him, negotiation becomes impossible.

Dr Eric Herring, the British author of Iraq in Fragments, a study released last year which charts Iraq's break-up into innumerable competing factions.

The whole thing is becoming increasingly localised, with people like Sadr being outflanked by extremists whom he can't control. It's possible that we may eventually remember Sadr as a moderate.

Telegraph