As the White House begins to rethink its policy on Iraq, savage new warlords are battling for power and the country is starting to splinter.As the self-appointed defender of his Shia kith and kin, his nom de guerre is "The Shield". But to his Sunni foes – and many of his own people – only one name does justice to the savagery with which Abu Deraa wages Iraq's sectarian war. He is, they say, the "Shia Zarqawi".

Less than six months after an American airstrike ended Abu Musab al Zarqawi's campaign of Sunni terror, an equally brutal fanatic has emerged on the other side of the religious divide. Abu Deraa's trademark method of killing is a drill through the skull rather than a sword to the neck, but his work rate is just as prolific as the former al-Qaeda leader's and shows the same diabolical artistry.

In the past year, he and his followers are thought to have murdered thousands of Sunnis, their victims' bodies symbolically dumped in road craters left by al-Qaeda car bombs. The rise of monsters such as Abu Deraa is another blow to American hopes that Zarqawi's death, in June, would halt the sectarian violence, which now regularly claims 100 lives a day.

In the strategy rooms of Baghdad's Green Zone, the question of how to stop the violence escalating into civil war has acquired renewed urgency since President George W Bush's losses in last week's US midterm elections, and his sacking of the defence secretary, Donald Rumsfeld.

Yet, according to diplomats, the Green Zone is no longer the powerhouse of bright ideas for the future of Iraq that it once was. Until as recently as last year, every ambitious state department intern and junior Foreign Office mandarin was keen to do at least a six-month stint there, keen to help forge democracy in one of the toughest environments ever. Today, though, the brightest and the best and have left, giving it the atmosphere of a place being wound down. Few up-and-coming diplomats, it seems, want "Iraq 2006" on their CVs, much less "Iraq 2007". One insider:

Working there is becoming like an albatross around people's necks. The feeling is that it doesn't matter how many hours a day they do, it won't make any difference. And nobody wants to be around if they end up getting helicoptered out, Saigon-style.

Meanwhile, out in the "Red Zone", as those diplomats now call it, residents face a future in which thugs such as Abu Deraa play an ever more prominent role. So great is the risk of being killed in tit-for-tat violence that Iraqi tattoo parlours are offering "death tags", showing names and next of kin. Such inkings are a safeguard against ending up among the countless -unidentified bodies in Baghdad's morgue.

Yet, while Abu Deraa may have replaced Zarqawi at the top of the American wanted list, Iraq's Shia-dominated government has shown a marked reluctance to sanction the kind of large-scale operation necessary to arrest him in his stronghold of Sadr City, a vast Shia slum in east Baghdad. Taking action against him could cost it valuable support among other Shia militias who, despite official disdain for Abu Deraa's bloodthirstiness, value the fear that such a loose cannon inspires in their enemies.

The worsening of inter-religious- bloodshed reflects badly on the Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Maliki, whose chief task when he took power in June was to win back Sunni confidence in the political process by stamping out the state's tacit backing of Shia militias such as the Mehdi Army.

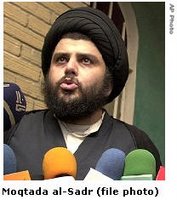

Yet, increasingly, men such as Abu Deraa appear to operate beyond anyone's control at all. He is among at least 20 former Mehdi Army commanders who are pursuing their own agendas, sometimes sectarian, often simply criminal. The former commander, Moqtada al Sadr, may be a thug himself, but at least he represented a single, identifiable authority. If dozens of freelance players emerge alongside him, negotiation becomes impossible.

Dr Eric Herring, the British author of Iraq in Fragments, a study released last year which charts Iraq's break-up into innumerable competing factions.

The whole thing is becoming increasingly localised, with people like Sadr being outflanked by extremists whom he can't control. It's possible that we may eventually remember Sadr as a moderate.

Association of Muslim Scholars'(AMS) Suleiman Harith al-Dhari, Iraq's leading Sunni cleric, who is wanted under an arrest warrant issued this month for inciting sectarian violence, accused the government on Saturday of bias.

Association of Muslim Scholars'(AMS) Suleiman Harith al-Dhari, Iraq's leading Sunni cleric, who is wanted under an arrest warrant issued this month for inciting sectarian violence, accused the government on Saturday of bias. Radical Shi'ite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr, whose Baghdad powerbase of Sadr City was the target of Thursday's bombs which killed 202 people, urged Dari on Friday to issue a fatwa, or religious ruling, prohibiting the killing of Shi'ites.

Radical Shi'ite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr, whose Baghdad powerbase of Sadr City was the target of Thursday's bombs which killed 202 people, urged Dari on Friday to issue a fatwa, or religious ruling, prohibiting the killing of Shi'ites. Sadr's aides also threatened to pull out of the government if Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki went ahead with a planned meeting with U.S. President George W. Bush in Jordan next week.

Sadr's aides also threatened to pull out of the government if Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki went ahead with a planned meeting with U.S. President George W. Bush in Jordan next week.